|

||||

What is Alzheimer's?

From (www.alz.org)

|

|

Inside the Brain: An

Interactive Tour |

- Is the most common form of dementia, a

general term for the loss of memory and other intellectual

abilities serious enough to interfere with daily life.

Vascular dementia, another common type of dementia, is

caused by reduced blood flow to parts of the brain. In

mixed dementia, Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia occur

together. For more information about other causes of

dementia, please see

Related Dementias.

- Has no current cure. But treatments for symptoms, combined with the right services and support, can make life better for the millions of Americans living with Alzheimer’s. We’ve learned most of what we know about Alzheimer’s in the last 15 years. There is an accelerating worldwide effort under way to find better ways to treat the disease, delay its onset, or prevent it from developing. Learn more about recent progress in Alzheimer science and research funded by the Alzheimer’s Association in the Research section.

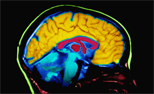

Alzheimer's and the brain

Just like the rest of our bodies, our brains change as we age. Most of us notice some slowed thinking and occasional problems remembering certain things. However, serious memory loss, confusion and other major changes in the way our minds work are not a normal part of aging. They may be a sign that brain cells are failing.

The brain has 100 billion nerve cells (neurons). Each nerve

cell communicates with many others to form networks.

Nerve cell networks have special jobs. Some are involved in

thinking, learning and remembering. Others help us see, hear

and smell. Still others tell our muscles when to move.

To do their work, brain cells operate like tiny factories. They

take in supplies, generate energy, construct equipment and get

rid of waste. Cells also process and store information. Keeping

everything running requires coordination as well as large

amounts of fuel and oxygen.

In Alzheimer’s disease, parts of the cell’s factory stop

running well. Scientists are not sure exactly where the trouble

starts. But just like a real factory, backups and breakdowns in

one system cause problems in other areas. As damage spreads,

cells lose their ability to do their jobs well. Eventually,

they die.

Learn more about Alzheimer's: Take the Brain

Tour

The role of plaques and tangles

Two abnormal structures called plaques and tangles are prime suspects in damaging and killing nerve cells. Plaques and tangles were among the abnormalities that Dr. Alois Alzheimer saw in the brain of Auguste D., although he called them different names.

- Plaques build up between nerve cells.

They contain deposits of a protein fragment called

beta-amyloid (BAY-tuh AM-uh-loyd). Tangles are twisted

fibers of another protein called tau (rhymes with

“wow”).

- Tangles form inside dying cells. Though most people develop some plaques and tangles as they age, those with Alzheimer’s tend to develop far more. The plaques and tangles tend to form in a predictable pattern, beginning in areas important in learning and memory and then spreading to other regions.

Scientists are not absolutely sure what role plaques and tangles play in Alzheimer’s disease. Most experts believe they somehow block communication among nerve cells and disrupt activities that cells need to survive.

Early stage and young onset

Early-stage is the early part of Alzheimer’s disease when

problems with memory, thinking and concentration may begin to

appear in a doctor’s interview or medical tests. Individuals in

the early-stage typically need minimal assistance with simple

daily routines. At the time of a diagnosis, an individual is

not necessarily in the early stage of the disease; he or she

may have progressed beyond the early stage.

The term young-onset refers to Alzheimer's that occurs in a

person under age 65. Young-onset individuals may be employed or

have children still living at home. Issues facing families

include ensuring financial security, obtaining benefits and

helping children cope with the disease. People who have

young-onset dementia may be in any stage of dementia – early,

middle or late. Experts estimate that some 500,000 people in

their 30s, 40s and 50s have Alzheimer's disease or a related

dementia.

History

At a scientific meeting in November 1906, German physician

Alois Alzheimer presented the case of “Frau Auguste D.,” a

51-year-old woman brought to see him in 1901 by her family.

Auguste had developed problems with memory, unfounded

suspicions that her husband was unfaithful, and difficulty

speaking and understanding what was said to her. Her symptoms

rapidly grew worse, and within a few years she was bedridden.

She died in Spring 1906, of overwhelming infections from

bedsores and pneumonia.

Dr. Alzheimer had never before seen anyone like Auguste D., and

he gained the family’s permission to perform an autopsy. In

Auguste’s brain, he saw dramatic shrinkage, especially of the

cortex, the outer layer involved in memory, thinking, judgment

and speech. Under the microscope, he also saw widespread fatty

deposits in small blood vessels, dead and dying brain cells,

and abnormal deposits in and around cells.

The condition entered the medical literature in 1907, when

Alzheimer published his observations about Auguste D. In 1910,

Emil Kraepelin, a psychiatrist noted for his work in naming and

classifying brain disorders, proposed that the disease be named

after Alzheimer.

Auguste D. |

Dr. Alois Alzheimer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

© Executive Home Care, Inc. 2001 - 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Executive Home Care, Inc. is a referral agency.

|